“I have a lot of experience with coaches trying to ‘ice’ me.”

-Graham Gano, Carolina Panthers

Introduction: Does Icing the Kicker Work?

Icing the kicker is something coaches have been trying for years. The belief is that calling a timeout before the kicker attempts a field goal forces him to sit on it and think a little bit longer. It seems as if each time a coach calls a timeout before a field goal attempt, the announcers talk about the opportunity to ice the kicker.

We examined numerous NFL games from the past five seasons (2014-2018) and NCAA games from 2018 to see if icing the kicker really does work, when the best time for a coach to call a timeout is, and if a kicker should attempt a practice kick before attempting the actual one.

Overall Icing of the Kicker in the NFL

Over the past five seasons, there have been 145 instances where the coach called a timeout in which his sole intent was to ice the kicker. In many cases, timeouts preceding a field goal were called to stop the clock and try to get the ball back and not with the sole reasoning to ice the kicker. For those instances, they are not counted in the data.

There have been an average of 286 NFL field goal attempts per season, with minimal variance from season to season, in the last 3:00 of the second quarter/fourth quarter and in overtime over the past four seasons (Sports Info Solutions has collected NFL data since 2015). Coaches only attempted to ice the kicker on about 10 percent of those kicks.

Of course, those coaches weren’t always in situations where they could or should ice the kicker, whether it be the game was already out of hand, the opposing team was out of timeouts, or another reason. However, only having 145 field goals that were iced in the last five seasons seems like a rather small amount given how much it gets talked about week in and week out.

Out of the 145 icing attempts, 85 of them came in the first half, leaving just over 41 percent of them coming in the fourth quarter or overtime. Coaches seem more inclined to use their timeouts in the first half without the game on the line, and the thought that coaches want to hold onto timeouts late in games in case they get the offense back on the field makes sense. Using them before halftime knowing there’s no immediate effect on the game and that three more timeouts are at your disposal once you come back out of the locker room seems more appealing.

What do the Numbers Tell Us About Icing the Kicker?

The overall yearly field goal percentage over the last five seasons sits between 84.1 percent and 84.9 percent (including postseason); with around 1,000 field goals attempted each year, that average is remarkably consistent. However, when we limit the data to only kicks in the final 3:00 of each half and overtime, the average drops down significantly.

Over the last four NFL seasons, icing the kicker has proven to be an effective strategy in clutch situations. Each year, the field goal percentage on iced clutch kicks was lower than that of non-iced clutch kicks. The closest gap came in 2015 at 8.1 percent, and the largest came the next season in 2016 when the gap was at 17.9 percent. The split for the 4-year average sits at 12.8 percent.

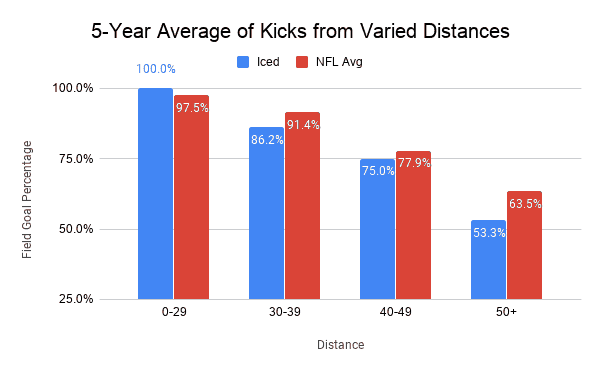

Yes, of course, icing the kicker does matter more at certain distances. The chart below shows the percentages of iced kicks from varied distances in comparison to the overall NFL average over the past five seasons. Anything under 30 yards is virtually a lock, regardless of a coach calling a timeout or not. If the opposing team has a chip-shot to win the game, it’s best to just pray for a bad snap or miss-hit and hope for the best. However, when you get beyond 30 yards, anything is fair game, with the biggest difference coming on kicks from 50 yards or longer.

When is the Best Time to Ice a Kicker?

There are varying opinions on when a coach should call a timeout to ice a kicker.

- Do you call the timeout before the kicker or kick team even get set up?

- Do you call a timeout as soon as they get set up?

- Or do you wait until the very last second and call it just before the snap?

All three options have merit and their own pros and cons as to why you should call it then. However, NFL coaches seem to take Option 2 most often.

Coaches called their timeout once the kicking team got set up more than the other two options combined. When you think about it, it makes a lot of sense: call the timeout when they get set up and before getting the chance to kick it and then make them have to go through the routine again.

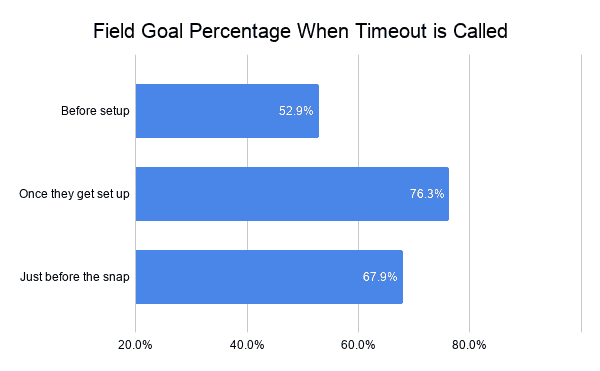

However, when looking at the numbers, kickers make the kick the most when the timeout is called then, at 76.3 percent of the time. It actually seems to be more beneficial to call the timeout before the kicker and/or kicking team gets fully set up. Kickers only converted on 52.9 percent of their kicks when that was the case.

Calling the timeout before the setup is a tactic that New England Patriots head coach Bill Belichick, Houston Texans head coach Bill O’Brien, and former Green Bay Packers head coach Mike McCarthy seem to use more than most.

In the last five seasons, Belichick has iced kickers six times and employed the strategy of calling his timeout before they get set up on three of those occasions, and twice he was successful. O’Brien has iced kickers five times, calling his timeout before the setup three times with success on two of them as well. McCarthy iced kickers six times, calling his timeout before the setup on four occasions, and again being successful two of those times.

Overall, former Cinncinati Bengals head coach Marvin Lewis leads the way with icing kickers 12 times (3 successful), twice as much as the next coach. Former Indianapolis Colts head coach Chuck Pagano has the best success rate of all coaches with more than two icings at 67 percent (4 out of 6).

Pagano liked to employ the strategy of calling his timeout at the last second, which he did four times and was successful on two of those attempts. Just 15 of the 45 coaches that have attempted to ice a kicker in the past five years have a success rate of 50 percent or better. New New York Jets head coach Adam Gase has been 0 for 6 in his attempts to ice kickers.

In terms of kickers, being iced has a bigger effect on some than it does others. When I asked Carolina Panthers kicker Graham Gano to answer some questions on this topic, he joked, “I have a lot of experience with coaches trying to ‘ice’ me.”

He’s definitely right, because he’s been iced eight times (making 6 of 8) in the last five seasons, tied with Blair Walsh (4 out of 8) for the most in the league. Gano, on if his mindset changes when he gets iced versus when he knows a timeout won’t be called, said “I never go out expecting for the coach to call a timeout. I go out every time the same way as a regular field goal.” He added that “game winners are exciting, but in reality, they are just like any other field goal and I treat it as such.”

Caleb Sturgis, who has kicked for the Miami Dolphins, Philadelphia Eagles, and Los Angeles Chargers during his career, is an 80.0 percent career kicker and has converted on all five of his attempts when being iced. Patriots kicker Stephen Gostkowski, known for being one of the better kickers in the league, is also perfect at 4-for-4 when being iced. Current Tamp Bay Buccaneers and former Los Angeles Rams, Chicago Bears, and Kansas City Chiefs kicker Cairo Santos has the worst percentage among kickers with at least one make when iced at 40 percent (2 out of 5).

To Take a Practice Kick or Not to Take a Practice Kick

My hypothesis and reasoning to start this research was to find out if kickers who take a practice kick when being iced tend to miss their actual kick more often than not. In just casually watching games over the past two seasons, it seemed like each time the kicker took the practice kick, he missed the actual kick. And it seemed to go both ways: if they get a snap but choose not to take the practice kick, they would make the actual kick.

The logic made sense to me. If a kicker takes a practice kick and misses it, now he’s in his own head and just visualized himself missing the exact kick he’s about to attempt. If the kicker makes it, he wasted a good kick and possibly gave the defense a look at the trajectory of his kick. The video below shows Rams kicker Sam Ficken missing a practice kick to the left and then over-correcting and missing the actual kick to the right.

Gano gave a different viewpoint. “If you take a practice kick, chances are you will not get that same ball back to kick again,” said Gano. “Usually [the first] ball is the better ball. Kickers don’t get to break the balls in for weeks like quarterbacks.

They are brand new before the game and our K-ball guy gets 45 minutes to break them in, so a good ball is very important. I have gone away from taking the first rep as a practice kick,” he added. “I realized that you are already prepared when you go out onto the field so it’s pointless to take a ‘practice kick’ before the real rep.” This makes a lot of sense and isn’t something I originally thought about going into the research.

If we define a “true opportunity” as when the long snapper has snapped the ball while everyone has stopped and the kicker is given the opportunity to choose whether to take the practice kick or not (the Ficken video above is an example of a true opportunity), we have a sample size of 40 kicks in the last five seasons.

When given a true opportunity and taking the practice kick, kickers made 58 percent of the actual kicks after the timeout (15 out of 26). On the other hand, kickers converted 93 percent (13 out of 14) when they were given a true opportunity and decided not to take the practice kick. The one miss came on a clear miss-hit by Ryan Succop in 2018.

As an aside, Baltimore Ravens superhuman kicker Justin Tucker is unaffected by this trend. He seems to go out of his way to take a practice kick when the ball is snapped and is 4 for 5 when taking a practice kick with his only miss coming from 65 yards. I guess it makes sense that the outlier, in this case, happens to be one of the best kickers of all time.

Icing the Kicker in College Football

When comparing icing in the NFL to the college game, the overall numbers differ slightly. In looking at the 2018 season in which at least one FBS team was a part of the game, the overall field goal percentage was 71.5 percent. Even when looking at just the clutch situations (final 3:00 of the second/fourth quarter and overtime), there wasn’t much difference, as the percentage sat at 70.7 percent. There were 112 kicks iced during the season. The percentage of makes on those kicks dropped all the way to 58.0 percent (65 out of 112), a 13.5 percentage point drop from the overall average.

Although the overall percentage is lower, the 13.5 percent difference is actually less than the 14.8 percent gap in the NFL, with the clutch differences being nearly identical with 12.8 percent in the NFL and 12.7 percent in college. A big rule difference from the NFL to college is the ability to call more than one consecutive timeout. 13 of the NCAA iced kicks came by way of the opposing coach calling two timeouts to ice the kicker, and those kicks were successful only 53.8 percent of the time (7 out of 13).

One of the most noticeable things when watching all of these kicks is that college coaches seem more inclined than NFL coaches to call timeouts on kicks under 30 yards. It happened 18 times in 2018 at the FBS level compared to only 8 in the NFL over the past five seasons.

The overall college average under 30 yards is 90.2 percent, compared to 97.5 percent at the NFL level. One of the possible reasons for this could be the wider hashes in college. Shorter kicks prove to be more problematic out on the hashes at the college level.

With this, college coaches don’t seem to have any distance limitations on when they attempt to ice a kicker, as it’s clear coaches in the NFL don’t bother as much with shorter kicks. When taking out NCAA kicks under 30 yards, the iced average sits at 51.1 percent, nearly a flip of a coin whether or not a kicker makes it from 30 yards or beyond after being iced.

Conclusion: Does Icing the Kicker Work?

Getting back into icing kicks by half, 50 of the NFL kick attempts were game-winning opportunities. Kickers converted only 64 percent of those.

24 NCAA kicks were for the win or tie, and kickers only converted on 54 percent of those kicks.

When looking at all of the numbers, coaches need to start taking a stronger look at icing kickers, especially late when the game is on the line.

Certain stats and analytics are beginning to change the way coaches coach during games, and I don’t see why this shouldn’t be one of those things that can carve more of a role in today’s game. The old adage of “play to win the game, don’t play not to lose” proves strong in this sense as well.

Be aggressive and use a timeout to ice the kicker instead of keeping them to use on offense in case they hit a go-ahead field goal. Using that timeout just might prove to be the “game-winner.”