NFL offensive play-callers generally plan out a set amount of plays to call at the start of each game, which is known as “scripting plays”. These “scripted” plays can be used in a specific order or called in specific situations the offense faces early on. They serve multiple purposes such as helping the offense or specific players get in an early rhythm, testing out and gathering intel on defensive adjustments, or helping a coach stick to a well thought out gameplan. Creating a well-planned script and then calling the right plays in game situations is the mark of a good play-caller. Here we will attempt to compare and evaluate teams by their scripts and in-game play calls.

Methodology

When describing his idea of scripting plays, the great Bill Walsh would use a “First-15” plays approach. For this evaluation, we will also use the first 15 plays as a proxy for a team’s script. We will then compare each team’s Expected Points Added (EPA) Per 60 Plays, which approximately equals one game, on these scripted plays to their performance over the rest of the game.

For this analysis, we also made a few minor adjustments to the plays that are included in the in-game sample of plays to adjust for context. The first adjustment we made was to remove plays within the last two minutes of both the first and second halves. We also remove any plays within the last three minutes of the 4th quarter if the score is separated by more than one possession. These plays were removed to control for teams either forcing passes downfield as time ticks down at the end of halves or trying to run the clock out at the end of a game. Neither of these situations provides an opportunity to accurately evaluate teams by offensive play calls.

Obviously, different play-callers are going to script a different amount of plays each week. They will also mix in-game play calls during the middle of a script when they find themselves in high leverage situations such a long third down. So using the round number of 15 as a proxy does have its limits. But, it should provide a general idea of which play-callers are maximizing efficiency at the beginning of games where plays are most likely scripted.

Scripted Plays vs. In-Game Plays

If we just look at the teams that performed the best within their scripted plays, we see some of the most efficient offenses from last season.

2018 Scripted EPA vs. In-Game EPA 60 Plays

| Team | Scripted EPA | In-Game EPA |

|---|---|---|

| Chiefs | 18 | 12 |

| Saints | 13 | 8 |

| Falcons | 10 | 2 |

| Packers | 8 | 2 |

| Rams | 8 | 10 |

Unsurprisingly, the Chiefs, Saints, and Rams were efficient both in and outside of their scripted plays. In contrast, the Falcons and Packers were extremely efficient within their scripts, but saw a significant dropoff on in-game play calls. This suggests Mike McCarthy and Steve Sarkisian were able to design a good script, but failed to provide the necessary adjustments once they had to call plays in-game. This might explain why both play-callers were replaced after last season.

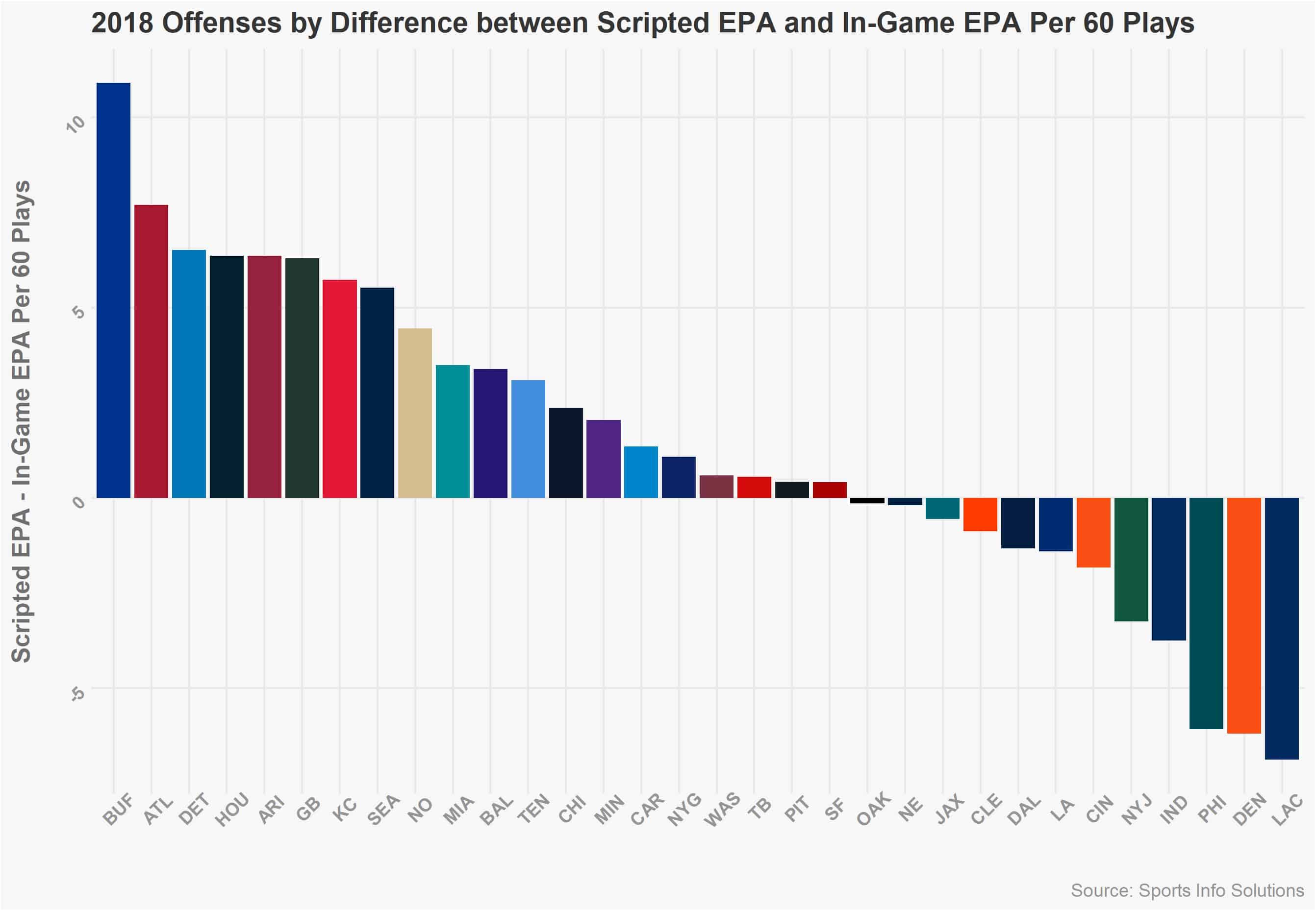

When comparing teams’ scripted play calls to their in-game play calls, we start to see some more interesting results at the top and bottom of the list.

Seeing teams that struggled on offense last season such as Buffalo and Arizona towards the top of this list should raise a few eyebrows. But, there is actually a simple reason they look good here: they were atrocious once they got past their first 15 plays. On in-game play calls, the Bills and Cardinals averaged an EPA Per 60 Plays of minus-12 and minus-13, respectively, by far the two worst teams in the league. In comparison, their scripted plays averaged a still not great, but much less abysmal, EPA Per 60 Plays of minus-1 and minus-6, respectively. This again is an example of play-callers who were unable to adjust once they had to call plays in-game.

Play Calling Comparison

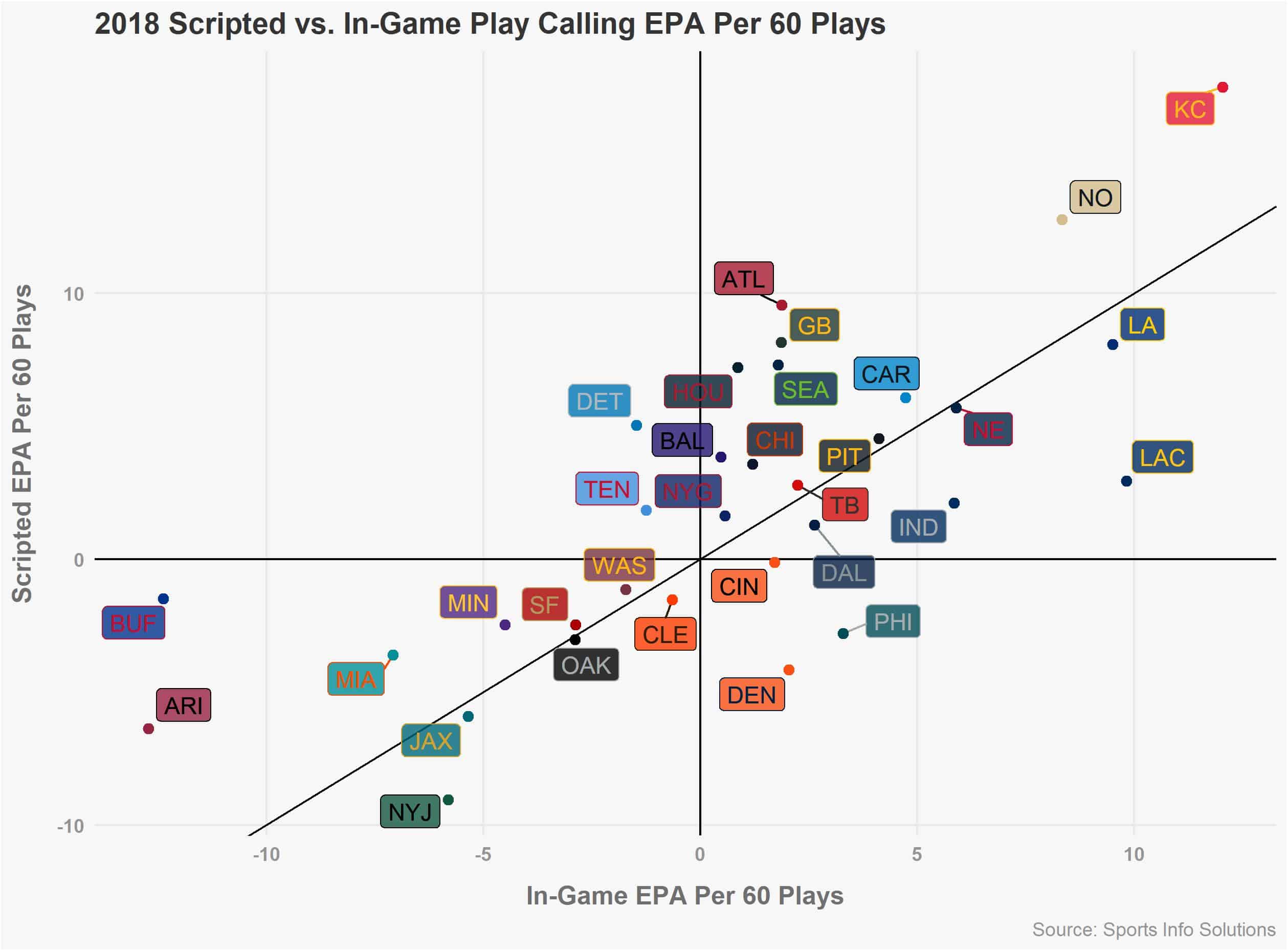

Due to the fact we are seeing some odd teams look really good by just showing the difference in efficiency between scripted and in-game play calls, let’s graph it another way for an overall evaluation. The below graph shows each team by how well they performed on both scripted and in-game play calls. This is a better way to show the results since it shows how each team performed in the two different situations.

With the above chart, we can compare teams’ play-callers if they were more successful within their script or calling plays in-game. The diagonal line represents a one-to-one ratio, meaning teams above the line generally performed better within their scripted plays and teams below generally performed better on plays called in-game.

As mentioned earlier, the Chiefs and Saints were the top teams in EPA Per 60 Plays on scripted plays. Here we see that even though the Chiefs and Saints both saw a decrease in efficiency on in-game plays, they were elite offenses in both situations. We also see a more accurate representation of the Bills and Cardinals offenses from last season. Although they were among the teams that saw a big leap in efficiency on scripted plays, they were still bottom-of-the-barrel offenses overall.

Conclusion

Since they are called at the beginning of games when there is a lot of time left, scripted plays by nature are not generally run in high leverage situations. But, they still serve a pivotal role for play-callers. They can get specific players involved in the offense early and they can show what look a defense will give against different formations or personnel. Getting playmakers involved early can establish an offensive rhythm, while getting a feel for a defense’s looks can provide opportunities for setting up shot plays later on in the game.

But no matter how well a play-caller scripts his plays, he still needs to be able to call good plays in-game. Otherwise teams, such as the Packers and Falcons last season, will move on to someone else. On the other hand, the best and most efficient offenses such as the Saints and Chiefs, led by innovative play-callers Sean Payton and Andy Reid, respectively, excel at both calling plays in-game and designing a script.